When we think about accessibility in the context of most built environments, the first thing that comes to mind for most people is whether wheelchair users can directly access the building via ramps, sufficiently wide doors, and elevators. But accessibility is, as we all know, involved much more than mobility access.

True inclusion and accessibility means considering hundreds if not thousands of combinations of physical, emotional, and mental abilities that are unique to every individual – involving not only our dexterity and mobility, but our constitution, sensitivity to noise, sensitivity to light, our ability to use one or more of our five senses, and much more.

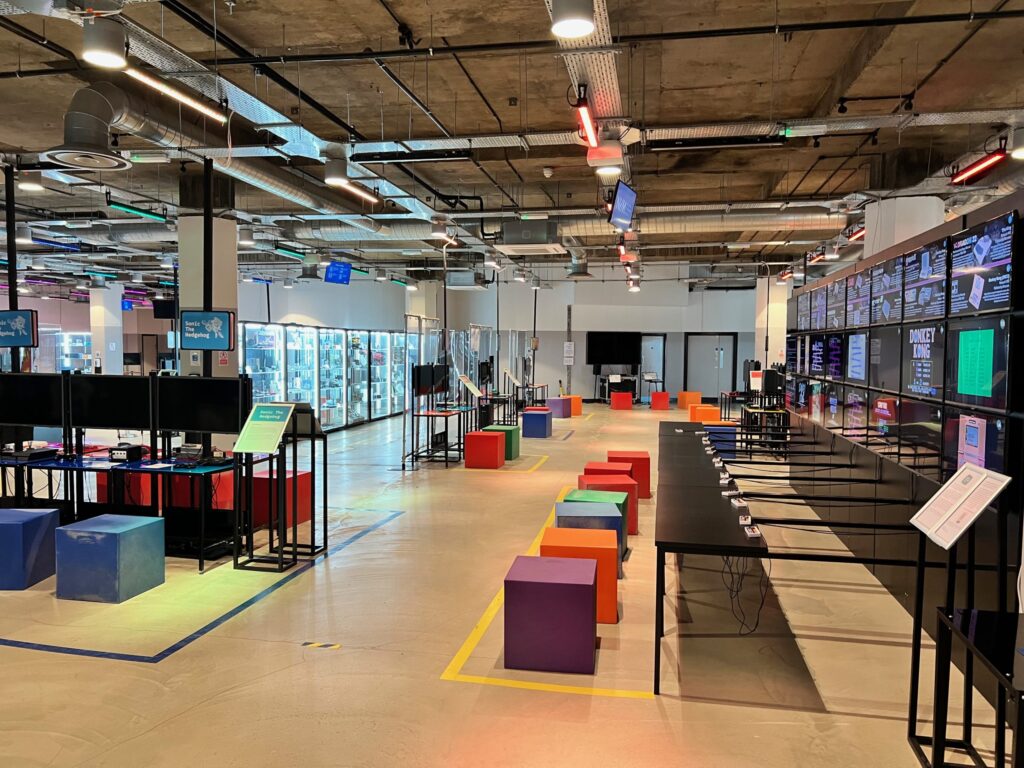

Accessibility in the context of museums and exhibits adds an extra layer of complexity to the equation – because not only does the physical architecture itself need to be accessible, but how exhibits are presented also needs to be considered by site owners. What’s more is that at peak times, museums will operate with heavy traffic – so considerations need to be made for the ‘ebb and flow’ of the space, where entrances and exits are, what the direction and layout of the pathways from room to room are like, how information is presented to visitors and where, what support is available on site and where it’s located, etc.

When Direct Access provides a site accessibility audit for a museum, we typically look at five base categories which normally apply to most sites, though every museum is different depending on its features, location, and even the culture surrounding the structure itself. For instance, if a museum is hosted within a protected building, this creates limitations for what exactly we are allowed to suggest as access consultants since Grade listed buildings are protected as sites of historic interest.

The five categories that we regularly consider are – general and physical access, communications and display, audio-visual presentations, lighting, and guidelines and legislation.

General and physical access is heavily regulated by the law, with different access standards specifying legal requirements for each element of the physical space. General and physical access typically incorporates everything from stair and ramp measurements to signage and orientation, to the visibility of glass manifestation glazes.

In terms of entrances and exits, level access should be maintained to ensure full wheelchair accessibility, with a clear approach and good circulation space on either side of the doors. In museum contexts, the visual presentation of exhibits and exhibit presentation is also considered, right down to the collision of certain colors and patterns on walls or carpets, which might be disorienting to people with specific disabilities. As mentioned earlier, the layout of the space is another key consideration – with specifications highlighted to ensure visitors don’t suffer fatigue or become overwhelmed by a complex floor plan.

Signage is another element considered under this category. It should be simple, short, and consistent in design and layout. Signs should contrast well with the surface they are mounted on, be well lit and be fixed at a consistent location.

Other elements reviewed under this category include the frequency, range, and placement of rest seating, the provision of accessible formats such as braille and hearing/induction loops, and escape/exit provision.

Communications and Display is another category which has specifications documented by several different pieces of legislation. It pertains to any instance of communication with a visitor to a museum, whether that’s in written or audio/visual formats. Additionally, it considers the positioning of the exhibits themselves – such as where an exhibit can be best viewed within a physical space, where sound effects and narration come from (as well as the volume and speed at which the information is communicated), and the typography, type style, type face and written language used in graphics, brochures, and information signs.

It also sets out standards for pictorial information, which is a necessary element of signage for people with cognitive impairments, dyslexia, and autism. At museums, we specify that photographs, illustrations, and other images should have a matt surface with clear images, have good contrast, be printed as large as possible, and/or have the important part of the image enlarged.

It is with this consideration also that we specify the need for large print brochures and leaflets, which are massively beneficial to older adults, people with visual impairments, and young children.

As the name suggests, audio-visual presentations are an accessibility factor that considers tape-slide, video, film, and computer/multimedia interactives) within museum and exhibit spaces. They are a commonly used method in most museums to communicate information in an informative and entertaining way, but can often be displayed without consideration for people with visual and auditory disabilities, by not providing subtitles, audio-descriptions, or transcripts of audio-focused experiences.

If any visual presentations are silent, a sign with this information should be provided, viewable within the AV area, to inform deaf visitors that they are not missing audio information. Presentations without narration but containing music that is significant to the presentation should provide the title of the music and any lyrics, as subtitles.

Recommendations in this category also consider potential disturbances to people who depend on hearing and induction loops to hear auditory information. These include fluorescent light fittings and heavy electrical cabling.

Lighting is a consideration that as the name suggests, takes into account the illumination of a museum space and its exhibits. Specifications detailed in guidelines in this category include how to correctly light entrances and main routes, light levels, light colours, and light maintenance.

Lighting levels are determined by factors including the material of the exhibits themselves, desired ambience, as well as accessibility needs of people viewing them, with a minimum lux level specified depending on the exhibit. In addition, the colour of the lighting is specified depending on whether the colour of an artefact is key to its presentation.

Lighting is especially important for groups that have visual disabilities, such as older adults and blind people. For this reason, any spaces designed to convey a dark, moody ambience with little lighting must not be on the main route which takes a visitor through the museum as well as all stairwells, entrances, and exits.

We typically recommend that museum spaces avoid unexpected shadows, glare, reflection or a crisscrossing of light sources, which create visual confusion.

Guidelines and legislation are the core foundation of a museum accessibility audit, helping us to clarify a client museum’s legal and statutory obligations – which in turn affect the structure and layout of an exhibition, and thus its interpretation by the general public.

Using guidelines and legislation, we can inform museum management of the regulations that are relevant to them, but we do not rely purely on this documentation, using it only as a blueprint from which we can help museums to go further and make best-practice accessibility adjustments that are meaningful, innovative, and future proof.

Due to the transient nature of legislation, it is not uncommon for our consultants to make recommendations that are not specified by documentation, as not all building standards are regularly updated, and many of them were written sometimes several decades before an audit before accessibility and inclusion was as acutely developed or considered by lawmakers.

Some examples of guidelines we refer to in our audits include; The Building Standards Regulations (and its variations for England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland), the Dubai Universal Design Code, the Disability Discriminations Act 1995, and the British Standards.

There is so much to consider when developing a museum exhibition when it comes to accessibility and inclusivity, which is why Direct Access has provided accessibility consultation to several museum and museum groups throughout the UK, including The Royal Armouries, the Science Museum Group, Horniman Museum and Gardens, the Harris Museum, National Museums Wales, the East Riding Museum Group, and multiple others.

To find out how we can help you make your site accessible and inclusive to all, get in touch with our award-winning team of consultants today.